How reframing inclusion criteria can help achieve representation in research

by Lauren Vamos, Operations Associate at Power

Improving diverse representation in clinical research is a major concern in the pharmaceutical industry. But what if the industry is looking for clinical trial diversity solutions in the wrong place?

Companies at the Collaborating for Novel Solutions (CNS) summit have converged on a few key areas to improve diversity in their trials:

- Enhance trust in communities by embedding community engagement year-round.

- Hire patient boards to give feedback on recruitment materials and protocol methods, thereby improving patient centricity of trials.

- Rebuild site networks to emphasize sites in diverse regions.

These methods are all excellent ways to improve recruitment numbers. But they may not be making much progress in improving randomization numbers.

Here’s a case study demonstrating why:

Socioeconomic factors like inadequate healthcare access, high rates of sedentary behavior, smoking, and diets high in fat, salt, and sugar all lead to higher chances of developing conditions like hypertension and diabetes. These conditions in turn lead to a higher risk of developing more serious conditions like stroke and neurodegenerative diseases.

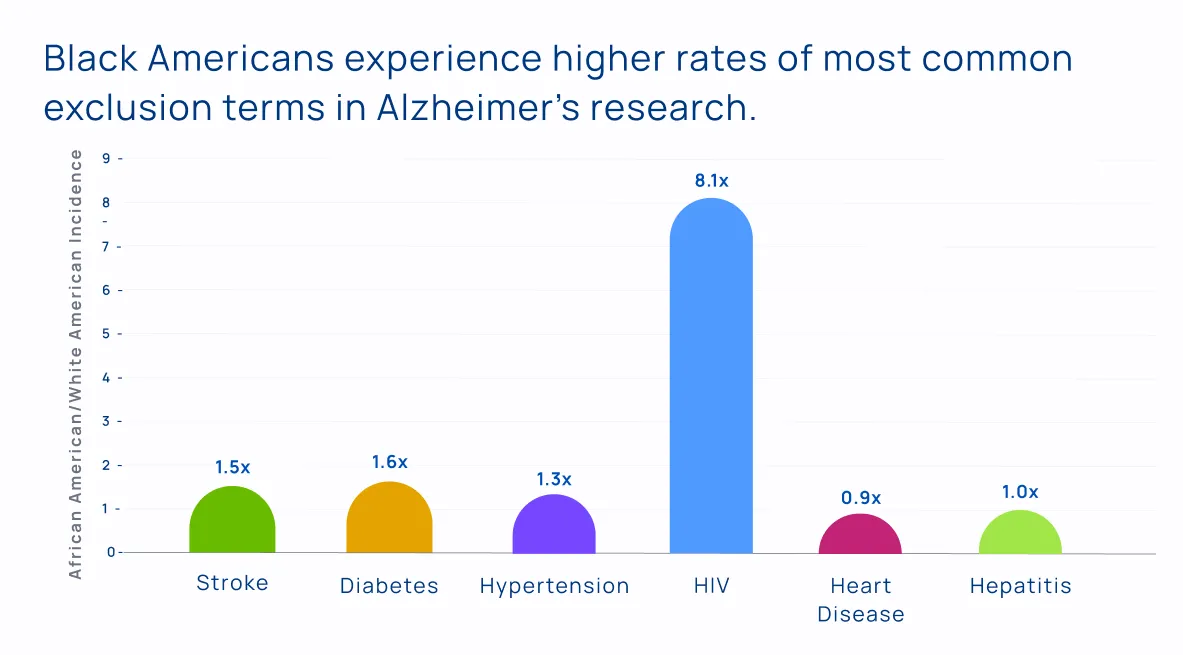

The end result: underrepresented, underserved, racialized populations have a much higher risk of developing a suite of chronic diseases. In 2018, Black Americans were 1.6x more likely than White Americans to develop diabetes, 1.3x more likely to develop hypertension, and 1.5x more likely to experience a stroke.

This trend works in a very insidious way when we start thinking about who can participate in clinical research. Many trials exclude patients with underlying health conditions like hypertension or diabetes. By doing so, these trials are excluding racialized participants at a much higher rate than White participants.

Consider an Alzheimer’s Disease clinical trial that is attempting to recruit a representative participant population:

Black Americans are up to 2x more likely to develop Alzheimer’s Disease than White Americans. The reason: risk factors for Alzheimer’s include a history of stroke, higher BMI, diabetes, and higher smoking rate. All these risk factors are experienced at higher rates by Black Americans.

The Power research team was curious if these same risk factors that caused high disease prevalence in Black Americans could also be excluding this patient population from participating in Alzheimer’s research. To find out, the team went into the national database for clinical trials in the United States, clinicaltrials.gov, and tallied every disease-related term that appeared in the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria sections of every Alzheimer’s trial in the database.

Since it is mandatory for trials in the United States to publish on this site, we had access to inclusion and exclusion criteria from every Alzheimer’s trial in the country over the past few decades.

We analyzed a total of 2,685 trials and discovered a few major inequities:

- Over 20% of Alzheimer’s trials exclude people with a history of stroke.

- Over 16% of Alzheimer’s trials exclude people with diabetes.

- Over 44% of Alzheimer’s trials exclude people with some form of cardiac condition.

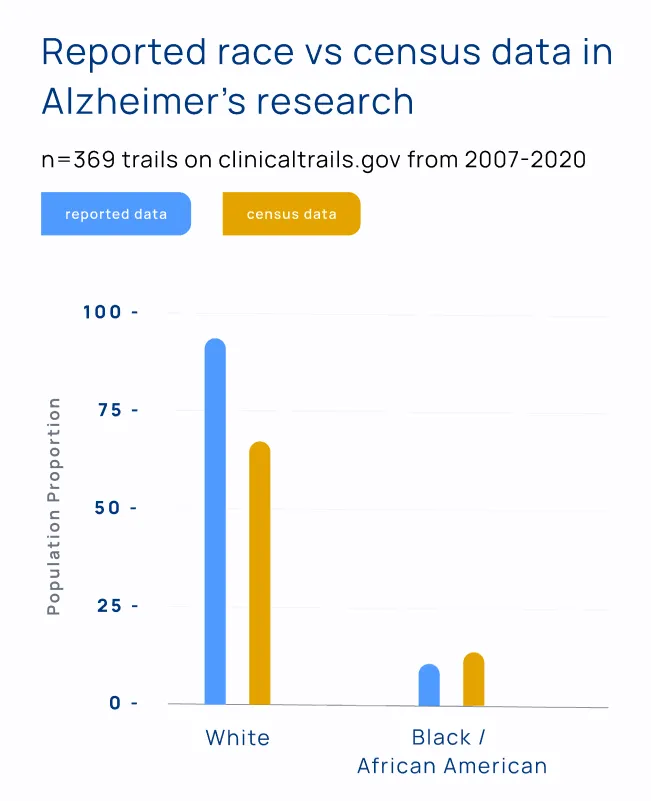

The result: despite an overwhelming proportion of disease burden in Black American communities, only 4% of clinical trial participants for Alzheimer’s research identify as Black or African American.

Investment in community engagement and site selection in diverse areas is a great step forward. But if all the new participants that companies reach through these new methods are screened out for underlying health conditions, this investment is worthless.

The exclusion of certain conditions in trials for certain interventions makes sense. Interventions that increase the risk of stroke should exclude participants with a history of stroke, for example. But most people who hear about this research agree that Chief Medical Officers and other protocol designers could think a little more critically about who they are really excluding when they implement blanket bans on chronic diseases in their research.

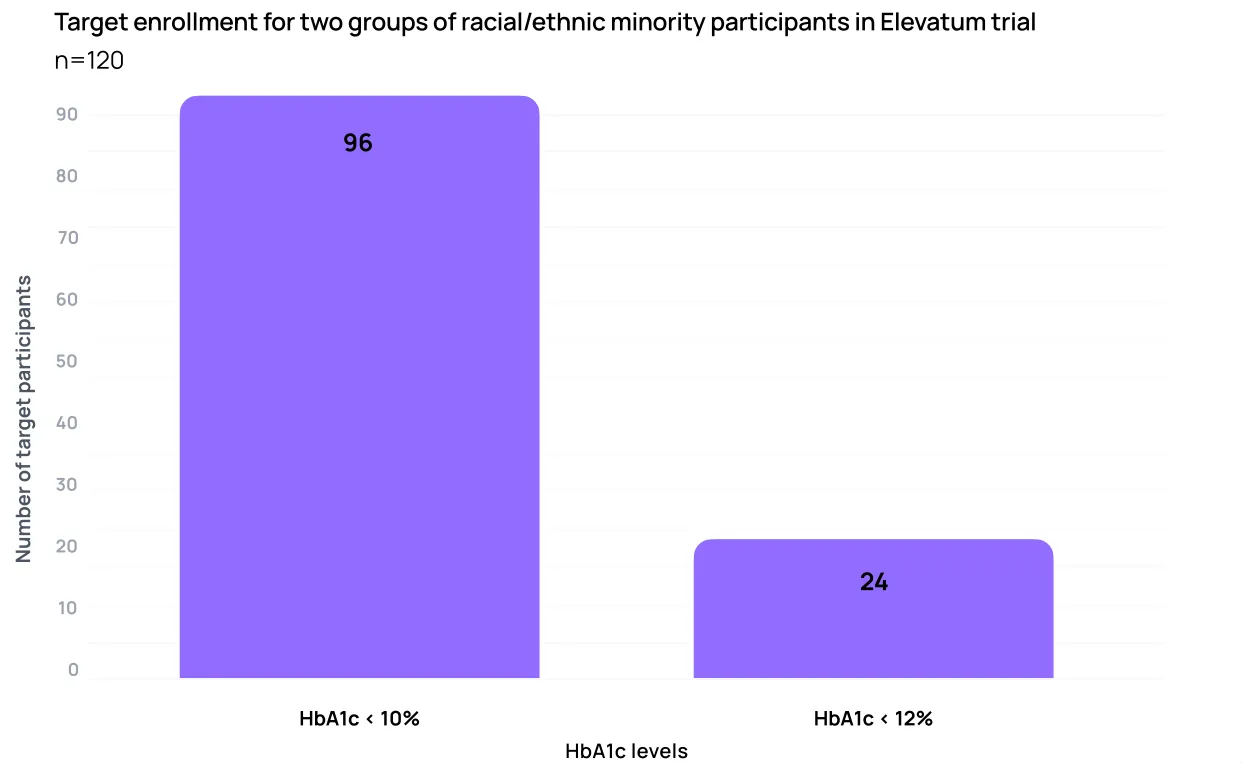

A great first step for companies looking for alternate ways to improve representation in their trials is to create two cohorts for later phase trials: a traditionally-recruited cohort, and a ‘real-world cohort’ with loosened inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Genentech is leading the charge on this methodology with a recent phase IV trial, called the Elevatum trial, for vabysmo, an Age-related Macular Degeneration and Diabetic Macular Edema drug. The Elevatum trial included one cohort with looser blood sugar restrictions in an effort to recruit more racialized participants, who have on average higher blood sugar (HbA1c) levels.

While we are still waiting for the final diversity results of these efforts, the idea is a logical (and much cheaper) step toward equitable representation in clinical research.

The research on the impact of Alzheimer’s comorbidities on Black American participation in research won the CNS summit 2022 poster committee competition.

This project is part of a larger initiative: a white paper on achieving racial/ethnic diversity in research co-authored with leaders from Genentech, PPD, and Stanford University. Check out the full white paper here: Achieving Representation in Clinical Research.

Lauren Vamos, Operations Associate at Power, CNS Summit 2022 Poster Committee Winner.