SDM Medical Abbreviation

What does SDM stand for in medical terms?

In the medical and healthcare fields, SDM is the abbreviation commonly used for “shared decision making,” a conceptual framework wherein patients and physicians both participate in and agree upon healthcare options in order to make decisions that are aligned with the patient’s values and preferences.[1]

An alternative SDM meaning is “substitute decision-maker,” which describes someone who is legally appointed to make decisions on behalf of a patient who is too ill or otherwise unable to make their own healthcare-related decisions.[2] In this article, we are discussing SDM as it refers to shared decision-making in medicine.

What is SDM in clinical research?

In the context of clinical research, shared decision making (SDM) can be one of the ways in which patients are given the option to participate in a clinical trial. As part of the two-way communication between the patient and his/her physician, the possibility of joining a clinical trial may come up as a choice that is available to the patients.

A 2022 report by the NCI/NIH indicated that the majority of patients (59%) would refer to their healthcare provider first to get information about clinical trial participation.[3] This positions physicians as one of the main channels of information about the possibility of participating in clinical research, and a major player in clinical trial enrollment. With the SDM approach actively engaging both parties in the decision-making process, the patient becomes more involved in decision-making and is able to play an active part in making healthcare decisions that are in line with their values. However, in order for SDM to lead to the option to enroll in a clinical trial, the patient’s physician must fit certain criteria:

- Be informed and aware of potentially suitable clinical trials

- Be willing to raise the possibility of clinical trial participation as an option for the patient (i.e., to consider that it is within their domain to suggest it)

- Feel comfortable suggesting “non-traditional” treatment options such as clinical trials

Not all physicians are open to suggesting clinical trial participation to patients, but for those who are, SDM provides a platform for weighing trial participation as an option against other potential decisions for the patient and identifying which option is the most aligned with the patient’s values.

What is an example of shared decision making in healthcare?

One example of SDM being implemented in practice is when a patient is newly diagnosed with cancer, and receives options from his/her doctor about potential cancer treatments available. Instead of simply accepting one treatment option proposed by the physician, they can use SDM as a platform to discuss various aspects about various options that are available and reach a decision together.

Hypothetical example of an SDM process in clinical care

John is diagnosed with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer, and his doctor informs him that he is a candidate for either radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or combination therapy (radio- and chemotherapy). Since each of these treatments has its own potential benefits and its own side effects/potential drawbacks, John’s doctor informs him about the risks and benefits of each therapy, such that they can reach a decision together that makes the most sense for John in consideration of his personal values. Let’s say the diagnostic imaging suggests potential metastasis but is unclear; John’s doctor may recommend systemic chemotherapy over localized radiotherapy, but John could share his personal perspective/desires and would have the right to decide to try localized radiotherapy first if he felt that the side-effects of chemotherapy outweighed the potential benefits, in his own judgment. Under an SDM framework, John’s doctor would not try to convince John that one option is more appropriate than another if it goes against John’s desires and values.

Steps involved in the SDM process

1. Inform the patient about the clinical picture and the options that are available

Usually, the conversation begins with the doctor informing the patient about the clinical issue at hand, i.e., what health issue needs to be addressed. Then, the physician will overview the potential treatments that he/she sees as plausible, although well-informed patients may also be in the position to suggest courses of action him/herself. The overview of available treatments should cover aspects such as:

- Potential benefits and dangers, and the risk-benefit ratio

- Timelines related to the possible benefits and risks

- Quality of scientific/medical evidence supporting each option

- Local availability of each option (i.e., potential travel requirements to receive treatment)

- Appropriateness of each option for the patient’s personal health/demographic characteristics

- Expected quality of life

- Any costs to the patient

After sufficient details about the options available have been presented, two main elements must be clarified before the decision-making process occurs: the risk associated with each decision/option, and the patient’s own system of values.[4]

2. Establish the core elements of SDM: Risk communication and clarification of values

In SDM, two main elements should be present: risk communication and clarification of values. Risk communication involves thoroughly educating the patient on the potential benefits and harms associated with each of the treatment options that is available. On top of this, it’s very important to clarify the patient’s individual values and take them into account in the shared decision-making process. An underlying principle of SDM is that the patient’s own beliefs should be valued and respected, even if those opinions don’t match with the medical evidence or perspective set forth by the physician.[4] The patient perspective could also include aspects of past experiences and current concerns.

3. Reach a clinical decision

With this information - the personal preferences of the patient and the medically informed opinion of the healthcare provider - there is a strong foundation laid for enabling them to collectively reach a decision that best suits the patient’s needs and values while still taking into account the medical expertise and evidence provided by the physician. This requires a unique skill of the physician - being able to provide informed guidance without dictating or mandating the eventual decision.

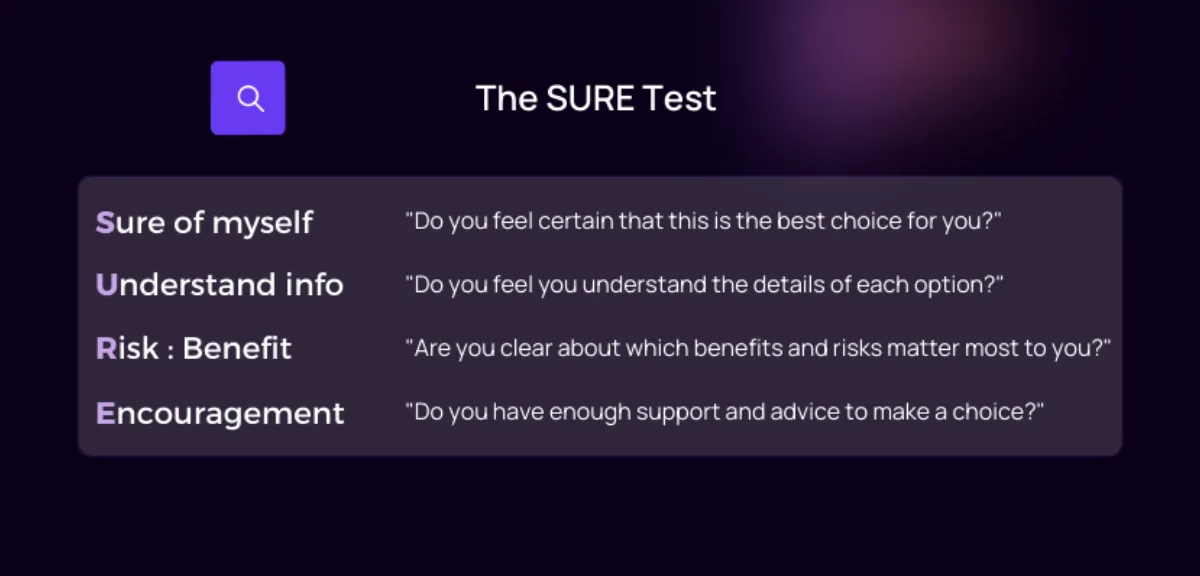

4. Confirm how comfortable the patient is through the SURE screening test

Once a tentative decision has been made, the SURE screening test can be employed as a supplementary measure to assess how certain and comfortable a patient is with the decision (i.e., to assess the risk of “decisional conflict”).[4]

Shared decision making model types

There are a few existing theories and frameworks regarding how shared decision making could be best implemented.

The Three-Talk Model[5]

The “three-talk” model of SDM is staged into three phases, beginning with a mutual agreement to work together and aiming to end with a decision being made. An example of the doctor’s communication is provided to describe each stage:

- Team talk - “We are going to work together, as a team, to describe choices, clarify your goals, offer support, and reach a decision that suits you.”

- Option talk - “We are going to compare the options available to you, based on a clear discussion of risk associated with each option.”

- Decision talk - “I want to know what matters most to you personally, and I will help you make an informed decision that is in line with your preferences.”

The Interprofessional SDM Model (IP-SDM)

The Interprofessional shared decision-making model (IP-SDM) applies a three-level framework to account for various influences (at the individual, systemic/organizational, and broader social/policy levels) when healthcare decisions involve various professionals from different disciplines, which is common in clinical care. More info on the IP-SDM can be found in the paper wherein it was proposed.[6]

The OPTION scale

The OPTION (“observing patient involvement in decision making”) scale takes a different approach, assuming that it is extremely difficult to determine if and when patients will actually want to participate in their healthcare decisions, in the case that they are actually feasible options available to choose from.[7] The OPTION scale takes the stance that the process of informing the patient about the possibility that they can - if they wish - influence the clinical decision-making process constitutes involving the patient. The OPTION scale can provide an indication of to what extent a clinician involves a patient in the SDM process, and can provide insights into the desire for the patient to be involved, without forcing patient involvement in the case that he/she prefers not to be actively involved.[7]

What are the benefits of SDM? Does SDM work?

Research suggests that implementing shared decision making processes leads to greater patient satisfaction while also improving adherence to treatment plans, in comparison to traditional models where patients simply follow clinician instructions without question or further discussion about available options. Other benefits that have been observed include improved education and knowledge, greater engagement and participation in decision-making, more accurate risk perception by patients, and more appropriate treatment decisions overall.[1]

In clinical research, the concept of patient-centricity has become a hot topic. SDM can be seen as a form of patient-centric decision-making, as it is informed by the patient’s experience and needs, and also actively incorporates their perspective. Improved engagement with one’s own health journey has been shown to greatly improve patient satisfaction, both within and outside of the context of clinical trials.[8]

Drawbacks and problems with SDM

Although shared decision making appears to be theoretically plausible and agreeable from the perspective of many healthcare professionals, few end up utilizing its full capabilities. A fundamental debate lies around the issue of whether it is actually appropriate to involve patients in decision-making - particularly taking the view that there are cases wherein the patient does not realistically have viable options to choose from, and should instead receive a guideline or the standard of care.[7]

In cases wherein SDM has been deemed appropriate and has been implemented, difficulties have been observed with shared decision-making due to its relative complexity compared to traditional directive healthcare, which may be related to various factors such as:

- Time constraints (not enough time for lengthy back-and-forth discussion in the traditional clinical model)

- Difficulties related to communication skills (empathy, compassion, legible patient-friendly language, and even language barriers)

- Inadequate training on the framework of SDM and how to implement it

- Insufficient consideration of medical experience and perspective (if the doctor allows the patient to take irresponsible decisions or fails to inform them adequately - the line between providing guidance and directing a patient to a specific decision can be rather blurry and hard to navigate)

- Attitude of physicians (willingness and interest in adopting SDM)[5]

Many of these challenges reflect commonly observed problems associated with the changing of social routines - healthcare is built on many traditions and well-established structures, and it can be a slow transition to break into new models of conduct. Ultimately, these hurdles must be overcome if SDM and patient-centric decision making are to make improvements in patient satisfaction. Widespread training of healthcare professionals, and standardization/regulation of SDM frameworks are two potential ways forward. For example, SDM is already more common in certain countries, such as the USA, Canada, and Germany, thanks to governmental and university training programs dedicated to shared decision making.[9]

Conclusion

In conclusion, shared decision making in medicine, or SDM, has the potential to improve upon our current healthcare landscape. Patients themselves are positioned to benefit the most due to greater involvement and engagement in taking decisions that are aligned with their personal perspectives and values - something that is generally lacking in the traditional healthcare settings dominating the clinical landscape today. However, there are prominent challenges to overcome in the implementation of SDM, particularly in relation to concerns about its appropriateness, health literacy of patients, and specific skill sets required of physicians. In the context of clinical research, SDM may represent an important avenue through which patients are informed about the possibility of enrolling in clinical trials, but this requires awareness and education amongst physicians.