A framework for incentivizing diverse recruitment

by Lauren Vamos, Operations Associate @ Power

Insufficient diversity in clinical trials results in financial consequences for all involved. Adverse drug responses cost the US economy $30.1 billion annually and sponsor-level costs incurred from FDA or insurance rejections increase the overall cost to stakeholders.

To better understand the financial impact of low diversity, let’s examine a case study: the Eli Lilly phase 3 trial for sintilimab was rejected by the FDA in 2022 for lacking a representative pool of participants because the original research was performed in China with participant racial demographics that were not reflective of the US. In light of this rejection, the FDA panel recommended Eli Lilly conduct another, more representative trial, with a price tag of hundreds of millions of dollars above the original research costs.

Despite an evident price tag, there have been no industry-wide efforts to financially incentivize better representation in research. Instead, change is motivated by FDA guidelines, which do not place any hard requirements on stakeholders and are therefore very slow at motivating progress.

As of 2013, 20 years after the National Institute of Health guidelines on representation began to be released, only 2% of all National Institute of Cancer trials had sufficiently enrolled participants from minority populations. As of 2018, only 13.4% of trials reported results based on race/ethnicity.

These trends demonstrate that the FDA guidelines, as they exist today, are not enough to move the industry to recruit representative patient populations. Incentives must accompany these guidelines to create real change.

Industry-wide change is unlikely without the proper incentive structures because sponsors would rather avoid the cost and risk of investing in diverse recruitment in pivotal trials before approval. Furthermore, public companies have a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value. Therefore, without explicit financial incentives, markets are unlikely to support investment in diverse recruitment.

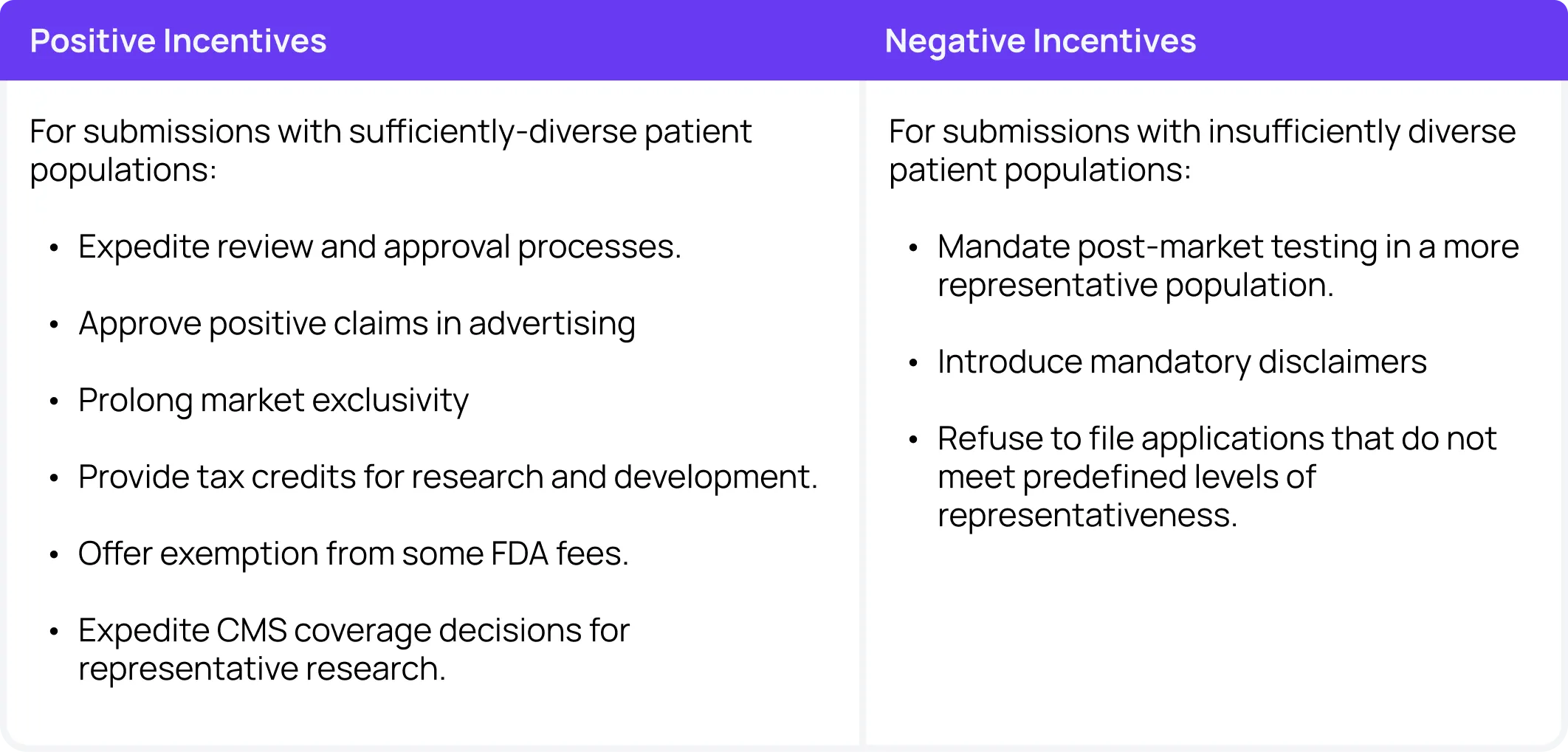

Since individual players are unlikely to make massive cross-industry strides, the FDA should be responsible for guiding change via incentives. The FDA is already providing guidelines to increase clinical trial diversity. The next step is to evaluate various incentives:

Positive incentives for diversity

Positive incentives will likely be met with less pushback from the industry, but require more substantial financial investment from governmental bodies. Options for positive incentives include an expedited review and approval process for submissions with sufficiently diverse patient populations. This expedited approval process would increase sponsors’ competitive advantage and offset any delays accrued by longer, more thoughtful diverse enrollment processes.

The FDA could also consider approving positive claims in advertising. For example, once a certain threshold has been met, sponsors could be allowed to advertise with the claim “This intervention has been tested in a representative population”.

This positive incentive requires minimal extra financial input and could be a valuable tool in competitive markets. This method also naturally improves data transparency for patients and caregivers and allows people to make a more informed choice about the interventions they choose.

Another positive incentivizing option is prolonged market exclusivity. While this method may become difficult in competitive markets where multiple players focus on diverse enrollment, it could be a crucial push for improved best practices.

The FDA could also consider providing tax credits for research and development for studies with sufficiently diverse patient populations. As an alternative financial compensation method, they could also offer an exemption from some FDA fees.

These options help offset the additional costs associated with larger investments in representative recruitment. Since the cheapest methods often recruit less representative participant populations, adding financial reimbursement options for these more thoughtful recruitment methods may be effective at promoting change without disincentivizing new research.

Finally, the FDA could consider working with CMS to expedite coverage decisions for interventions that have been tested on sufficiently diverse patient populations. As a major coverage provider, CMS is a crucial player in the ultimate financial success of an intervention.

For example, due in part to the lack of diverse participants in phase I-III trials for Adulhelm, CMS recently determined that they will not cover the Biogen Alzheimer’s drug unless patients are enrolled in a trial. A lower demonstrated efficacy in phase III also helped guide the decision. This move cut potential consumers from a projected 50,000 to less than 5,000, resulting in massive losses from projected models.

Overall, positive incentive options are the best bet to ensure sponsors aren’t facing massive cash deficits by investing in diversity. Providing some compensation for incentives for participating in research studies, for example, could ensure that patients receive more adequate reimbursement without a larger cost incurred by the sponsor. Since better reimbursement packages are more effective at recruiting a more representative patient population, these mechanisms are crucial to improving industry best practices.

Negative incentives for diversity

Negative incentives may not be the best choice across the board because they often work to disincentivize new or difficult research and new entrants into the market. However, in extreme cases, they may be effective at maintaining base standards of representation in clinical research.

One option for studies with insufficiently diverse patient populations is mandatory post-approval testing in a more representative population. This method is useful because often sponsors find it difficult to rationalize extra investment in diverse recruitment in early phase trials before they have any certainty that the intervention will end up successful in the market.

Requiring more representative testing post-approval means that sponsors will be financially able and likely willing to rationalize some extra spending on additional testing as the interventions enter the market and start to return on their investment.

The FDA could also consider introducing mandatory disclaimers like “This intervention was not tested on a representative population”. These disclaimers may incentivize sponsors to invest in recruitment upfront to attract a larger consumer base later. They also help patients and caregivers make more informed decisions about their medications.

Finally, as an extreme negative incentive, the FDA could consider setting minimum standards and refusing to file intervention applications that do not meet minimum diversity requirements. These minimums would likely need to be reflexive and dependent on the disease and population in question and only operate in more extreme circumstances.

The best options

It is worth noting that negative incentives will often work to slow overall progress and disincentivize new entrants to the market, whereas positive incentives may spur innovation. The FDA should understand that major players will be able to invest more upfront in diverse recruitment, while smaller companies may find it more difficult to change their recruitment practices. Therefore, positive incentives in the form of financial compensation, positive claims in advertising, and expedited review processes, could be the most effective way to change industry practice without slowing progress.

Incentives for new, innovative clinical trials that emphasize novel recruitment and methodologies will help decrease costs per trial over time while ensuring therapies benefit all types of people who will one day use them. As a tangible first step, industry players and the FDA could collaborate on a set of clinical trial compensation guidelines to begin building a robust incentive framework.

Learn more about alternate methods to improve diversity in research by reading the full report.