Your session is about to expire

Blinding in Clinical Trials

Blinding, also known as masking, refers to withholding information about assignments of participants to study groups in a clinical trial. Blinding is a core consideration in clinical trial design, and is a common yet arguably underused methodological technique that serves to minimize bias and ensure the reliability of study results in clinical trials. Read on to find out everything you need to know about blinding - why and when it’s necessary, what purposes it serves, who can be blinded, and how it’s done (and undone).

What is the purpose of blinding in clinical trials?

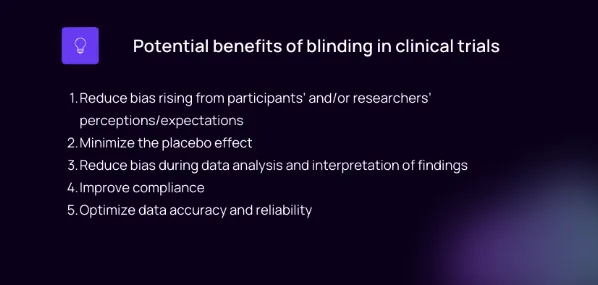

The primary purpose of blinding is to prevent one or more parties involved in a clinical trial – participants, investigators/physicians, outcome assessors, or a combination thereof – from being influenced by knowledge of the treatment assignment or intervention received during a trial. This reduces the risk of bias – a systematic deviation of data or results from the “truth.” The following section lists 5 major reasons why blinding may be used in a clinical trial.

5 purposes of blinding in clinical trials

1. Blinding can reduce various forms of bias

Blinding can help minimize or prevent bias associated with expectations or preconceived notions about an intervention or placebo, helping to ensure that any observed effects are genuinely due to the treatment being investigated rather than influenced by psychological factors, behavioral modifications, or preferences. Blinded studies can thus reduce subjective biases and performance bias, increasing the overall validity and credibility of the clinical research findings.

2. Blinding can minimize the placebo effect

Blinding helps control for the placebo effect - a phenomenon where individuals perceive an improvement simply through the belief that they are receiving an effective treatment. By preventing participants from being aware of their assigned group, they are less likely to change their behavior or report on their symptoms through a lens that is tinted with that knowledge. Thereby researchers can better evaluate if a particular intervention truly leads to improvements beyond what would be expected through placebo alone.

3. Blinding can reduce observer bias

Another type of bias, observer bias (or detection bias), can be reduced through blinding by ensuring that the data analysts or outcome assessors who evaluate study endpoints or outcomes remain unaware of which treatment group participants belong to. This eliminates potential for bias arising from expectations of the data analysts, and maximizes impartiality (neutrality) in assessing outcomes. This is important for generating truthful, reliable scientific evidence. Analysts are generally blinded in triple-blind studies, along with participants and researchers.

4. Blinding can increase compliance

In certain cases, blinding can promote participant compliance with study protocols since they may be less likely to deviate from assigned treatments based on their preferences, such as wanting to avoid certain exposures.

5. Blinding can help optimize data accuracy and reliability

Blinded studies tend to produce higher-quality data because they minimize measurement or detection errors that could arise if researchers, clinicians, or patients consciously or unconsciously alter their behaviors due to knowledge of their assigned interventions. Minimizing deviations between groups includes trying to prevent participants from drastically altering their behavior, which could significantly change the study outcomes in an invisible (undetectable) manner since those factors were not monitored as part of the study design. This increases the accuracy (truthfulness) and thus the reliability of the data and the results of the study. Since clinical trial results are often used to make decisions on new drug approvals and to inform healthcare guidelines, it’s important that the data used to inform these decisions be as reliable and accurate as possible.

When is blinding necessary?

Blinding is particularly necessary when subjective outcomes are evaluated in a clinical trial, as these may be more prone to bias than objective outcomes (such as death). Subjective outcomes are those that rely on subjective assessments or observations made by participants, healthcare providers, investigators, or analysts. Common subjective outcome measures include pain levels, quality of life assessments, and symptom severity. These outcomes depend on the outlook and perceptions of the person making the assessment, even when there are formalized scales designed to measure these outcomes.

Subjective outcomes are more prone to bias since an individual’s perceptions and expectations can influence how they might report or evaluate these outcomes. A lack of blinding in clinical trials with subjective outcomes presents a relatively high risk of bias as people may unconsciously rate their symptoms or experiences based on their knowledge of which treatment group they’ve been assigned to.

Objective outcomes, such as mortality rates or specific laboratory measurements, are less at risk of bias when blinding is not used, since these are less dependent on individual perceptions and less influenced by expectations.

Is blinding the same as randomization?

The relation between randomization and blinding

Randomization is the process of methodically assigning study participants to study groups in a random manner, which serves to minimize differences between treatment groups. We’ve written extensively about randomization in this article.

Randomization minimizes variation in confounding variables across treatment groups, and thus works to minimize a type of selection bias that could arise from assigning participants to groups based on anything other than an entirely random procedure. However, randomization does not prevent bias arising from the investigators or study physicians from treating participants or interpreting results differently between groups. Thus, blinding is often used in combination with randomization in order to prevent bias that could originate from:

- Differential treatment of participants between groups

- Certain participant behaviors based on knowledge about their assignment

- Differential analysis of data and interpretation of findings based on knowledge of the treatments assigned

Allocation concealment vs blinding

Allocation concealment refers to the process of withholding information about group assignment until the time at which the assignment is formalized. Blinding, in contrast, refers to the withholding of this information until after the study is completed (or even perpetually).

Blinding types in clinical trials

Unblinded study (open-label study)

An unblinded study, more commonly known as an open-label study, is a type of clinical research study where both the researchers and participants are aware of the intervention assigned to each participant. In open-label studies, no attempt is made to hide treatment assignments, and all parties involved know who is receiving which treatment or intervention. These trials can be useful in certain situations where masking is not considered necessary or feasible, such as in single-arm studies (involving only one intervention and thus only one group) or when evaluating certain surgical procedures or lifestyle interventions. For more about unblinded studies, see: Shedding Light on Open-Label: The Role of Unblinded Studies in Clinical Research

Single blinding in clinical trials

A single blind study is a type of trial design in which either the participants or the investigator(s) remain blinded, while the other knows about the treatment allocations. For example, in a single-blind study, participants might not know whether they are receiving an active drug or a placebo, while the study’s healthcare providers and outcome assessors are aware of what each participant is receiving. Such a single blind study design might be used when it’s important for objectivity that participants don’t know what they’re receiving, while that information is important for the investigators in order to make ethical care decisions and uphold patient safety.

Double blinding in clinical trials

Double blind study definition: Neither the participants nor the researchers involved with the trial know which participants are receiving which treatment or intervention until after data analysis is complete.

Double blind studies aim to reduce the risk of any potential biases due to preconceptions, expectations, or preferences of either the participants or the researchers. The group allocations remain concealed using coding systems or by a third-party, until after all data collection and analyses are finalized. Sometimes, blinding may be maintained indefinitely, but usually unblinding is performed at a given point after study completion. Some argue that this is an ethical decision in that it allows participants to have the full information about their participation in a double-blind study.

Single blind vs double blind

To summarize, in single-blind studies, only one group (either the participants or the researchers) are blinded to treatment allocation throughout the duration of the trial, whereas in a double blind study, both groups are unaware of participant allocations.

Triple blinding in clinical trials

Triple-blinding takes blinding one step further than double blinding. In triple blind studies, not only are participants and researchers unaware of treatment allocations, but those involved in the final statistical analyses are also blinded. This helps prevent any potential bias during interpretation of the results due to knowing which treatments were associated with specific outcomes. Blinding of analysts may be important for certain studies more prone to detection bias or reporting bias. It usually requires an additional step of coding the database before database lock, so that analysts do not have access to information about treatment allocations.

What is an example of blinding in research?

An example of blinding in research can be seen in the case of a study evaluating the effectiveness of a new pain medication compared to a placebo for menstrual pain. In this trial design, participants are randomized into two groups: one receiving the active medication (treatment arm) and another receiving a placebo (placebo arm). It’s decided that both researchers should be blinded. In other words, this study is a double-blind study, or more specifically a double blind randomized controlled trial (RCT).

In order to perform and maintain the double blinding, the following actions would be taken:

- The sponsor would provide identical-looking pills to the investigators who distribute them to participants. One contains the active pain medication, and the other is the placebo (it looks the same but does not contain any active medication)

- Participants are given their pills, but would not be informed whether they are receiving the pain medication or the placebo.

- The investigators/healthcare providers responsible for administering the medications, recording participant data, and assessing outcomes would also remain unaware of the assigned treatments. They are given the pills for each patient with a coded identification, i.e., “XY223” rather than the drug name or “placebo.”

-Throughout the trial, neither the investigators nor the participants will know whether each participant is receiving placebo or the active pain medication.

By effectively maintaining blinding throughout this study, researchers can obtain less-biased and therefore more-reliable data to indicate whether the new pain medication provides better pain relief compared to the placebo. The participants are less likely to make certain adjustments to their behavior or report their symptoms differently due to the influence of knowing what they are taking. For example, if John Smith knows he is taking the active pain medication, he may imagine his pain levels are going down even though they are the same as before the study (i.e., a placebo effect). If Suzy Smith knows she is taking the placebo, she could decide that she needs to give herself more frequent and longer self-massages to reduce her pain since she is not taking any pain meds, which could lower her self-reported pain levels, thus presenting a confounding bias (an influence on study results that is hidden in unobserved behaviors or characteristics).

When can you break the blind in a clinical trial?

Normally, specific rules about when a blind can be broken are described explicitly in the trial protocol. This process, also known as unblinding, means that one or more of the groups who were blinded (participants, researchers, or analysts, or a combination thereof) is unblinded - they are informed about the group assignments that had been made. Unblinding is normally conducted in order to permit more accurate assessment of outcomes by giving investigators more complete information, or for ethical or safety reasons where it’s necessary for assignments to be revealed.

Controlled unblinding describes when the unblinding procedure is planned in accordance with a specific event, whereas emergency unblinding is done when an unforeseen circumstance arises that requires assignments to be revealed. We have written in more detail about unblinding in clinical trials here.

Conclusion

Blinding is one of the main aspects of clinical trial design, and refers to “blinding” – withholding information from – either participants, researchers, and/or data analysts to the allocation of participants to treatment groups. Blinding plays a critical role in minimizing bias and ensuring the reliability and validity of clinical trial results. It is particularly important when subjective outcomes are assessed in a trial, in order to minimize the influence of personal perceptions, values, preconceptions, and preferences on the subjective outcome measures. The choice of blinding type depends on the specific study design, its objectives, and the characteristics of the intervention being investigated, but the goal remains the same – to optimize the accuracy and reliability of clinical trial findings.